A sector deep dive on the recent history of upstream energy, and an overview of its drivers and current investment grade private debt financing landscape.

Pendulum of perception

Upstream energy serves as the genesis for the conventional energy value chain, but it can be a volatile sector characterized by boom-and-bust periods and shifts in creditor sentiment between optimism and pessimism. After a turbulent decade capped by the Covid-19 pandemic, the credit profile of North American energy companies has seen significant improvements and as such the pendulum of investor perception is swinging back towards the positive.

Combined with a dearth of bank capital, this has provided opportunities for private investors— especially those such as Voya with deep expertise in complex reserve-based securitizations.

In this Energy & Infrastructure Insight, we provide a grounding in the recent history of the upstream energy sector, as well as an overview of the evolving private financing landscape, along with its risks and potential rewards.

Unleashing American energy

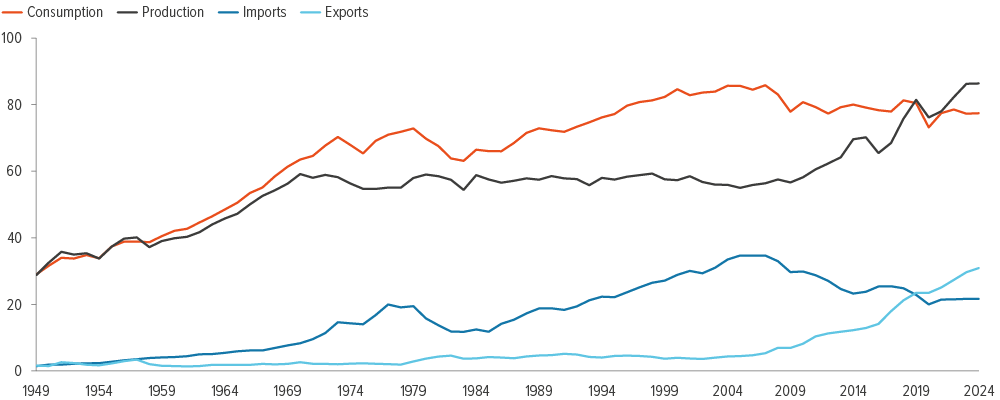

Prior to 2019, the United States was a net energy importer, relying on foreign countries to meet domestic energy needs, a trend that had persisted since 1952. U.S. energy imports peaked in 2005, when the U.S. imported ~30% of the energy it consumed. Since 2005, energy imports have waned, culminating in the U.S. becoming a net exporter of energy in 2019 (Exhibit 1).

The United States’ shift from net importer to net exporter was driven by the adoption of enhanced recovery techniques, namely hydraulic fracturing and directional drilling.

Source: Energy Information Administration.

The theory behind hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” came shortly after Edwin Drake’s discovery of oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859. The first attempt at fracturing hard rock surrounding oil reservoirs can be traced to 1865, when Edward Roberts filed a patent for an “oil well torpedo.” Roberts’ torpedo was designed to enhance oil well productivity by fracturing subterranean rock formations, releasing oil trapped within them. Over the next 140 years, while oil giants such as Halliburton filed additional patents for enhanced oil recovery techniques, the process remained largely unused.

The industry changed when George Mitchell combined hydraulic fracturing with another energy innovation, horizontal drilling. Mitchell’s initial success involved the drilling of horizontal wells in the Barnett Shale outside of Fort Worth, Texas.

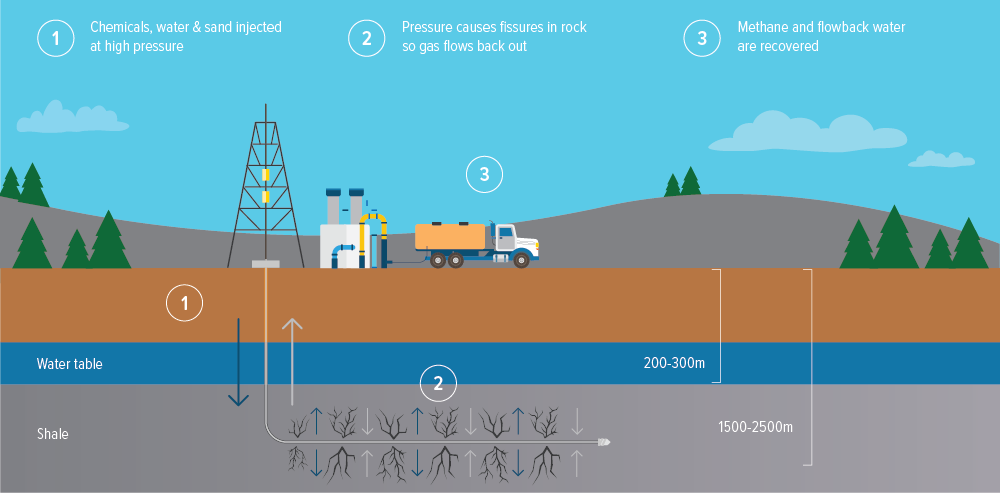

Mitchell’s teams would drill horizontal wells which they would then “frack” by shooting a mixture of water, chemicals and sand down the wellbore at high pressure. The fracking process would cause targeted shale rock formations to fracture and release “tight” oil and gas trapped in smaller pockets within the shale rock that would have been uneconomic to lift using conventional drilling techniques.

The long “laterals” resulting from the horizontal drilling process allowed Mitchell’s teams to enhance the amount of oil and gas recoverable, as they were able to tap into a longer range of reservoirs than could be accessed by vertical drilling (Exhibit 2).

Prior to Mitchell’s discovery, there was widespread concern that the U.S. would deplete its energy endowment. By changing drilling methods, a broader array of formerly uneconomic reserves became highly economic.

According to the Independent Petroleum Association of America, enhanced recovery techniques have been used to develop over 1.7 million wells in the U.S., which have produced over 7 billion barrels of oil and over 600 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. In 2022, hydraulic fracturing accounted for ~66% of U.S. crude oil production and ~80% of U.S. dry natural gas production, according to the Energy Information Administration.

Source: Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit.

Growth at an (un)reasonable price

Much like the California gold rush in the 1800s or Silicon Valley in the 1990s, new entrants rushed in. Mitchell’s process was quickly adopted by upstart independent exploration and production (E&P) companies backed by private equity capital. The independent E&Ps further augmented Mitchell’s techniques, combining them with directional drilling, artificial lift and other technological innovations to further enhance hydrocarbon recoveries from individual wells.

If Mitchell’s process was the match, then directional drilling and other advances were the gasoline that acted as an accelerant for the shale boom. The confluence of these technologies allowed upstream companies to target new formations at a much lower cost, changing the energy landscape forever.

Voya underwrote its first infrastructure transaction in 1990 and, since then, the energy & infrastructure team has remained a core pillar of our investment grade private credit offering. We manage a circa $13 billion portfolio that focuses on single or multi-asset secured financings through a traditional project finance structure, plus investments in corporations whose business models have infrastructure characteristics. Since Voya began classifying deals into infrastructure, corporate, and ABF in 2002, the infrastructure team has maintained a zero credit loss rate—successfully preserving principal through commodity cycles, financial crashes, geopolitical shocks, and the pandemic, while also generating competitive returns. The team has deep sector experience across the energy and infrastructure landscape developed over multiple decades of transaction underwriting. It is our pleasure to distill that expertise into this series of educational insights for our current and prospective clients. |