Voya’s investment leaders debate the Fed rate cycle, policy questions, and the widening effect of AI’s massive, global buildout.

Markets are scaling fresh highs at the very moment the economy is losing steam. Payroll growth has slowed to a crawl, jobless claims have drifted higher, and the housing market remains challenged. Yet investors seem undeterred, buoyed by the promise of rate cuts, resilient corporate earnings, and the extraordinary and unrelenting surge in capital spending tied to artificial intelligence. This contradiction is the backdrop for our CIO roundtable. Our panel begins with the Federal Reserve’s delicate balancing act: remaining vigilant on inflation while openly acknowledging risks to employment. As the conversation turns to policy, it’s less about tariffs (what a shift from April!) than about the pressures on U.S. institutions, from Fed independence to fiscal sustainability and the role of the dollar as a release valve. The panel debates why the U.S. continues to lead global markets, with American companies generating unmatched free cash flow. We examine how the race to build AI data centers is spilling into public and private financing markets—and where that may create future vulnerabilities. And while tech has dominated, we ask whether market leadership can finally broaden —into cyclicals, staples, and small caps. Housing earns its own focus, as CIOs weigh the drag from locked-in mortgages against the potential for a rebound if rates slip below 6%. Welcome to this wide-ranging discussion, which reflects both the unusual resilience of this cycle and the risks that linger beneath the surface. Eric Stein, CFA |

Shifting focus from inflation to jobs

Stein: We got the 25 basis point cut markets expected, but the dots1 and Powell’s press conference told a deeper story: less worry about inflation, more about employment.

Reinhard: Right, the Fed chair essentially shifted the balance of risks toward the labor market and away from inflation. We see this as a dovish pivot and a meaningful change in direction of Fed policy. The market quickly priced in multiple rate cuts over the next year. (We expect two more this year.) And it gave a boost to corners of the market that have lagged this year, such as U.S. small caps, value stocks—anything that hadn’t ridden the tech-led hyperscaler rally.

Easing inflation concerns and growing labor strains have cleared the way for further rate cuts.

Hobbs: What struck me was the new Trump-appointed Fed governor calling for much lower policy rates. It showed the political element creeping in and the pressure to cut rates more aggressively.

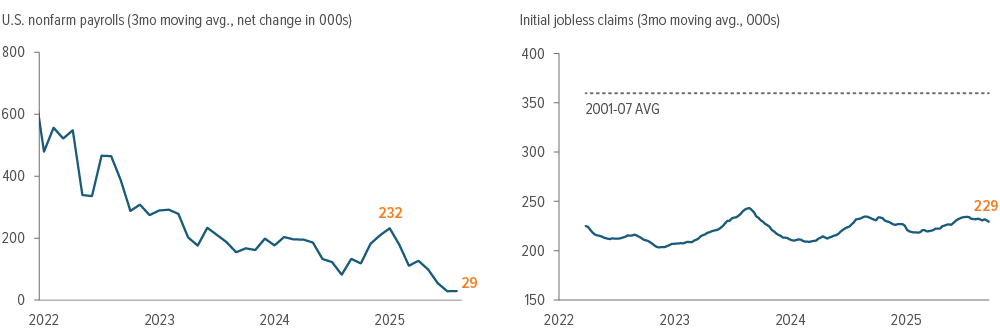

Reinhard: Labor is the key driver. Payrolls have faded to a 3-month average of 29,000, from over 230,000 at the start of the year. But jobless claims, which are a more real-time gauge, are sitting around 230,000. That’s still nowhere near the pre-GFC average of 360,000 from 2001 through 2007. Our sense is that the labor market slowdown has been more about the moment’s unique circumstances: immigration policies, uncertain trade policy, and some employers taking a wait-and-see approach to hiring while they figure out how much efficiency AI can deliver. The claims data tell us we are in the clear and that recession risks aren’t rising meaningfully.

Hobbs: It’s a strange mix. We’re in a low-hiring/low-firing environment. Demand for labor has weakened, but supply has also shrunk, partly due to immigration curbs. You want to watch for warning signs of a much weaker labor market. If labor data is consistently being revised downward, future data will likely go in the same direction. Also, unemployment rates for subgroups such as younger workers—many of whom don’t show up in new claims data, because they’ve never had a job—sometimes signal broader weakness ahead.

Stein: Jim, as rates come down, that’s good for stocks, particularly small caps. But how much of the rally is just markets discounting future earnings streams at lower rates?

Lydotes: I think it’s more than lower rates, because you’re seeing specific stocks trade up after giving cautious guidance. There was a lot of complacency in the market heading into the Fed meeting. The market hasn’t been listening to what management teams have been saying about inflation pressures and consumers.

As of 08/30/25. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Restoration Hardware’s CEO flat-out said you have no idea the inflation that’s coming in the fourth quarter for hard goods with long inventory cycles. Olive Garden’s parent, Darden, is experimenting with smaller portions and lower entry-price points. It says to me we haven’t seen the worst of the inflationary impact, yet stock prices are brushing that off.

Concerns about institutional credibility would likely show up in a weaker dollar.

Hobbs: Credit markets are also signaling a mid-cycle expansion. They’re looking ahead to an economic boost in 2026 from tax cuts, the Big Beautiful Bill, and the deregulation impulse. It’s not normal to have investment grade yields this low at the same time that spreads are this tight. That’s not a market expecting an imminent recession.

Reinhard: From a macro investing standpoint, the time to really overweight small caps is when the economy is pulling out of a recession. That’s when small caps are traditionally poised for significant outperformance.

Stein: The framework is tricky, though: a slowing job market against sticky prices. It’s a textbook conflict in the Fed’s dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability

Fed leadership and fiscal discipline under scrutiny

Stein: Six months ago, the world was obsessing about tariffs. Today, the bigger questions are around domestic institutions and policy.

Reinhard: We’ll have to see what the Supreme Court decides on tariffs next year. But even if struck down, the administration probably has ways to keep tariffs in place. The One Big Beautiful Bill should offset some of the drag, especially for the higher-income households that drive spending.

The real policy wildcard is the next Fed chair. If markets read that appointment as politically aligned rather than academically anchored, it could cause some nervousness should the current account deficit widen.2 If the market revolts, we would likely see it in the dollar weakening versus other currencies.

Stein: I agree, the dollar acts as the release valve for policy uncertainty. Normally, you see it in long-term bond yields, but that largely hasn’t happened yet. The problem is that the rest of the world has issues, too, so there aren’t many clean alternatives.

Hobbs: In fixed income, we’re generally focused on defending the downside, because the upside is getting par. What’s happening is that this administration is simply more comfortable with policy actions that break precedent. It hasn’t hurt markets so far, but things that have made America the premier destination for capital for generations—the rule of law, open markets, institutional independence—those are all being pressured. It widens the range of potential outcomes.

The bigger issue long term is fiscal math: No administration has had the discipline to stabilize debt-to-GDP. You could have a scenario next year where the labor market deteriorates and nominal growth is slower than debt growth. Then those questions of sustainability will come front and center. It’s the kind of thing that will simmer on the back burner until one day it becomes the only thing markets care about.

And politically, it’s not far-fetched to imagine an election-year fiscal transfer: “Look at all the tariff money we’ve raised, here’s a check.” The electorate might like it, but markets probably wouldn’t.

Stein: So it seems that in this cycle, positioning around policy risk is less about guessing tariff details and more about guarding against a credibility gap, with the dollar as the barometer.

Reinhard: Which loops back to the Fed focusing on the labor market. If the new chair leans political while jobs soften, the bar for further rate cuts stays low.

AI buildout goes global

Stein: Let’s connect the macro story to what’s going on in markets. Despite all these questions hanging over the global economy and geopolitics, stocks are setting records.

Coyle: And it’s not just the U.S. It’s a global bull market. The S&P 500 is near all-time highs, and so is the MSCI ACWI ex-U.S. Even China’s back, and it’s not just muddling through on another round of state-driven investment—it’s participating in the same AI infrastructure buildout that’s powering the U.S. rally.

Kaczka: We still like U.S. equities over international markets. U.S. companies are generating free cash flow that you just can’t replicate elsewhere. Even with the enormous growth in capex for the hyperscalers, those megacaps are still expected to produce a nearly 16% free cash flow margin over the next 12 months.3 Then you add in a shareholder-friendly culture. It’s a big reason to stay domestic.

Stein: How much of U.S. outperformance is simply that we’re better at tech, and tech is what’s driving the world? Europe doesn’t seem to be innovating at scale. It’s got like one GLP4 company and a big chipmaker, but those are the exceptions. What’s holding it back?

Lydotes: Regulation is a big part of it. The Draghi Report noted that from 2019 to 2024, the EU passed 13,000 new rules, compared with about 5,500 in the U.S.5 That gap has weighed on European equities. But I think Europe is getting a wake-up call due to Trump’s tariffs and the growing security threat. The tone around regulations and fiscal spending is improving, and you have the AI buildout coming their way, because they don’t want to send their data outside any more than Americans do.

Coyle: I still prefer China over Europe. That’s not something I would’ve said in recent years, but China is leaning aggressively into AI, which is the single biggest trend we’ll see play out over the next five years. Google said in July that its Gemini model is pushing nearly a quadrillion tokens a month, double the pace of the previous quarter.6 You’re seeing headlines of truly massive data center deals, and we’ve really only been in the training phase. The real tidal wave is AI inference—demand for tokens and compute is exploding, and the capacity isn’t keeping up.

Stein: Jeff, you’ve been focused on how AI investment is being financed. Where’s the money coming from?

Hobbs: Up to now, hyperscalers could self-fund out of trillion-dollar equity market caps and internal cash flow. But the scale of the need is now so large they’re tapping debt markets, and they’re going to shift some of that debt off balance sheet. You’ll see this borrowing demand spill across every corner of fixed income—corporate credit, private debt, ABS, CMBS7 —wherever borrowers can find the most efficient capital. That’s both an opportunity and a risk, because whenever you have this level of debt growth, it won’t always go smoothly.

Stein: Like the internet cycle in the late ‘90s.

Hobbs: Right. The internet transformed our lives, but plenty of bondholders lost money along the way. It’s the same setup here: AI will transform the economy, but not every type of financing will be a winner. Eventually, we’ll overbuild capacity. And tomorrow’s data centers may not need the same footprint as the ones being built today.

People like to frame it in terms of what inning we’re in, but you never see a baseball game where someone makes a spectacular play in the fourth inning, so they just skip ahead to the seventh. Leaps like that can happen with AI, like the DeepSeek announcement, that change the trajectory.

Stein: So what do you do to mitigate that risk?

Hobbs: Two things: We’re being very judicious about where we lend—in specific markets, with specific developers, with high-quality counterparties, while limiting risk to residual asset valuations. We want to know that cash flows from the lease will fully pay down our debt over the life of the lease term, with someone well qualified ready to take off the loan. We don’t want to be dealing with refinancing risk for 10-20 years on a data center where we don’t have a strong sense of its forward valuation and where secondary use cases for the facility can be at significantly lower values.

And because it’s a theme that straddles both public and private markets, we’re ensuring that our public and private credit teams are looking at this together. Because without a well-coordinated platform, you could end up taking risk in places that are inefficient.

Cyclicals and small caps set for a pivot

Stein: What I’m hearing is that this isn’t just a tech sector story. Where does leadership go next? Are we finally seeing signs the rally is broadening?

Lydotes: Tech’s performance has been justified by the data, and I’m not about to bet on a major reversal there. But other areas look interesting, too, such as consumer staples. The sector has struggled this year on both the fundamentals and sentiment. But at this point, the negativity is largely priced in. For example, Pepsi is trading at its lowest relative multiple in 25 years. Sometimes things don’t have to get good— they just have to get less bad. If inflation eases and the consumer stabilizes, staples could surprise on the upside.

Sentiment has been so poor for consumer staples that things just need to get less bad to see an upside surprise.

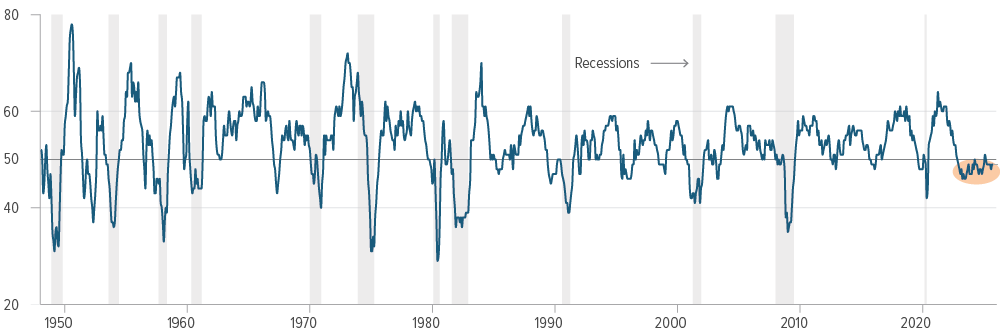

Stein: So a value play in staples. John, you’ve been talking up cyclicals. What’s the case there? Coyle: I see a major pivot into cyclical companies over the next 6-9 months. PMIs8 have been stuck below 50 without a recession longer than any point in recent history. Normally, readings that weak would have coincided with a contraction by now, but instead, I think we’re set up for an inflection higher.

So far, the AI trade has been fueled by the scramble for compute and utilities selling off all their excess capacity. We need more capacity, and that expansion should spill over into cyclicals that have lagged over the past year. Energy is part of that. Everyone’s bearish on oil, but how are we powering these data centers? It won’t be one source. It’ll be solar for speed to market, natural gas for scale, and everything else in between.

Lydotes: All of that infrastructure goes through a permitting process that’s highly regional, passing from federal agencies to states and cities that control rights of way. I think we’re going to continue to see policy around building out AI infrastructure. It’s creating a regulatory bull market around the entire energy utility space.

Stronger fundamentals plus further rate cuts should be a good mix for cyclicals and small caps.

Reinhard: The bond market is also looking supportive. Long-term yields have been steadily declining all year, and cyclicals tend to do much better than defensive sectors in that type of environment.

Coyle: Four of the ten best years for the S&P 500 happened when the Fed was cutting but the economy wasn’t in recession.9 That’s the sweet spot we may be entering now. If that holds, cyclicals and small caps could be real leaders for the next leg.

Kaczka: One thing our team has been debating is how much rate relief small caps will need to really make a difference. It’s a tricky balance, because you need growth strong enough to push up nominal GDP, because small caps are more sensitive to that. But you also want the labor market soft enough to give the Fed cover to keep cutting.

Small caps do tend to have shorter debt maturities because they have more floating-rate exposure. So, in theory, they should benefit from a cutting cycle. But the reality is their effective interest costs are still rising. If intermediate rates remain where they are, and if companies keep rolling debt at higher coupons, the drag on margins could actually be worse for them than for larger caps. So it isn’t as straightforward of a setup as “rates go down, so small caps go up.”

Coyle: To me, it’s less of a rate call and more of an earnings-driven story. In the second quarter, the “S&P 493”—excluding the Mag 7—grew earnings by 8%, when expectations were for 2%. For the second half of 2025, we expect mid-single-digit earnings growth. That’s why I’m pretty comfortable with earnings multiples at 20x next year’s estimates.

As of 09/30/25. Source: FactSet, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

What could break the housing holding pattern?

Stein: Housing is another big issue affected by interest rates. It’s been kind of stuck since the post-Covid run-up over issues of low affordability and high mortgage rates. Where do you see that headed?

Hobbs: The lack of affordable supply is keeping a floor under home prices. The problem is that housing starts weakened after the 2022 rate-hiking cycle, and construction no longer contributes much to growth. Lately, construction has handed off from housing to data centers.

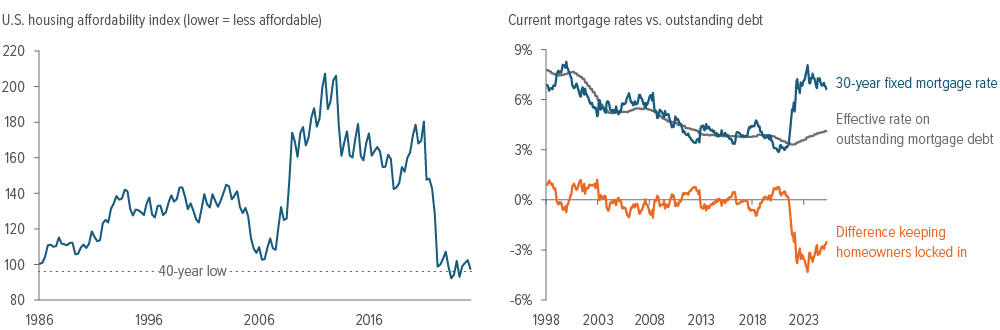

Reinhard: Affordability just continues to plague the housing market. The small decline in mortgage rates has prompted an uptick in loan applications. But the effective rate on all outstanding U.S. mortgages is approximately 4%, whereas a new 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is about 6.4% (see chart). That difference keeps most homeowners locked in place.

Housing turnover is less than it was before the global financial crisis, running at about four million homes per year.10 What we need is for mortgage rates to decline far enough to entice the incremental new buyer. That would ignite the housing market, and then the ancillary factors such as home appliances and furnishing demand would follow.

Coyle: In my opinion, the risk is asymmetrical to the upside. Housing has been in recession for over two years. For all the people who bought homes back in 2019-21, life has happened in the years since—their family grew, and the three-bedroom house no longer works. Each year that passes, the slingshot gets pulled back further. If we get to spring selling season with a mortgage rate below 6%, that could be a significant driver of economic activity that no one’s really anticipating.

You also have the president floating a “national housing emergency.” He’s already declared ten national emergencies since taking office. Why not tack on an eleventh in housing? It wouldn’t surprise me to see some kind of policy intervention or the Fed buying mortgages again. So I see the risk skewed to the upside. If it goes down from here, it would be like falling out a basement window, whereas few people seem to be asking what could go right.

As of 09/24/25. Source: Bloomberg, Voya IM.

Hopes and fears

Stein: Let’s close out with a quick round-robin on what concerns you and what excites you for the rest of 2025.

Lydotes: My biggest concern is complacency, especially around the consumer and inflation as we head into the holidays. Companies are signaling caution, but markets aren’t listening. If inflation proves stickier or the consumer retrenches harder, that’s trouble. What excites me is small caps. They’ve already taken the pain from inflation and tariffs, and they’re positioned to benefit if uncertainty clears. I love that setup going into next year.

Reinhard: I’m a bit worried about the Fed appointment. A political placement at the top could undermine its credibility, which could flow through the financial system, because everything is benchmarked off the Treasury market. However, the market is still really healthy. It’s already had a 20% correction and I think it would take a major economic shock to get another one in the near term. I’m also not worried about inflation—the AI boom will be disinflationary in the long run.

Kaczka: My concern is that the market may get impatient with the payoff from AI capex. Even with strong free cash flow margins, sentiment could turn if growth rates slow while spending continues to ramp up. But I do believe the AI theme has room to run. The buildout is massive, transformative, and global.

Coyle: Jobs data will stay sluggish, and skepticism will linger. But I believe we’ll see an inflection in PMIs, and that will drive cyclicals in 2026.

Hobbs: The prospect of fatter tails under this administration—a wider range of asymmetrical outcomes—is concerning, because in fixed income, we’re generally focused on downside protection. Could we end up with policy that the market just can’t digest?

What excites me is the commercial real estate lending opportunity. After years of challenges, activity is finally picking up. The real estate cycle normally lags the corporate credit cycle, but this time real estate corrected first due to secular pressures in offices and the weight of higher rates. The NCREIF Property Index is still 10% off and three years out from its peak while the rest of the market is going strong.11 So the spreads you can get with commercial mortgages are pretty interesting.

On the public side, the yield curve is going to get out of its weird check-mark shape and get back to normal with the outlook for economic expansion. Investment grade yields at 5-6% make the world go around.

Stein: My concern is fiscal credibility— globally, but especially in the U.S. If term premiums rise and bond markets start to doubt institutions, that’s bad for all assets. What excites me is the possibility that inflation comes in lower than expected. That would free the Fed to cut further, regardless of politics, and provide a tailwind across markets.

Thanks everyone for another engaging discussion. For our readers, a few takeaways: Keep an eye on jobless claims and the dollar. The AI capex trend still has legs, but cyclicals and small caps look interesting. And watch for imbalances and overexposures in your portfolio.

Have a great rest of the year, and we’ll check back soon for your thoughts on 2026.