Key Takeaways

Asset-based finance (ABF) is private lending with the structural protections of securitized credit and the covenants of investment grade private placements.

It offers a significant amount of shorter-weighted-average-life paper as well as a wide range of collateral.

Recent growth in the ABF market is a healthy result of banks stepping back from traditional lending areas, but there are risks around changes in banking regulation and new managers overpromising.

We cut through the hype to give you real answers about ABF: what it is, how to allocate to it, and where the risks are.

The ABF renaissance: Everything old is new again

What is ABF?

Asset-based finance is a decades-old market designed to provide financing for assets, both real and financial, through structured vehicles optimized for both lenders and borrowers.

While there may or may not be recourse in the structure to the owners of the assets, ABF underwriting is based on ring-fenced cash flows derived from a specified pool of assets.

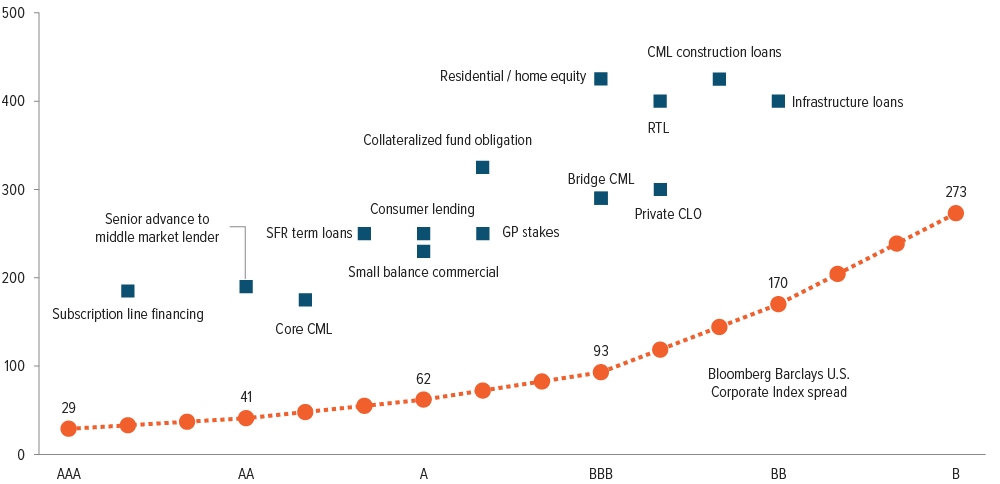

As of 08/22/25. Source: Bloomberg Barclays, Voya IM.

In essence, ABF uses techniques from public securitized markets, such as aspects of CLO structuring, and applies them—along with additional covenants— to private lending. By putting collateral in a rated debt finance structure, ABF gives non-bank lenders access to collateral types that they previously couldn’t lend against.

As it is a private structured product, ABF tends to be priced with both a structural premium and a customization premium that makes it attractive relative to investment grade private credit and public securitized credit (Exhibit 1).

For most of ABF’s long history, it was best suited for banks and life insurers from a capital efficiency standpoint. It wasn’t really marketed as its own brand—it was simply the more structured, asset-heavy end of the private placement and leveraged loan spectrum.

For example, back in 1992, Voya’s investment grade private credit team was doing highly structured private lending secured against ring-fenced pools of receivables from timeshares and MRI equipment leases. That was ABF, but it wasn’t called ABF then.

If ABF is decades old, why am I only hearing so much about it now?

The reason ABF is having a moment in the spotlight is due to large increases in both borrower and lender interest in non-bank channels.

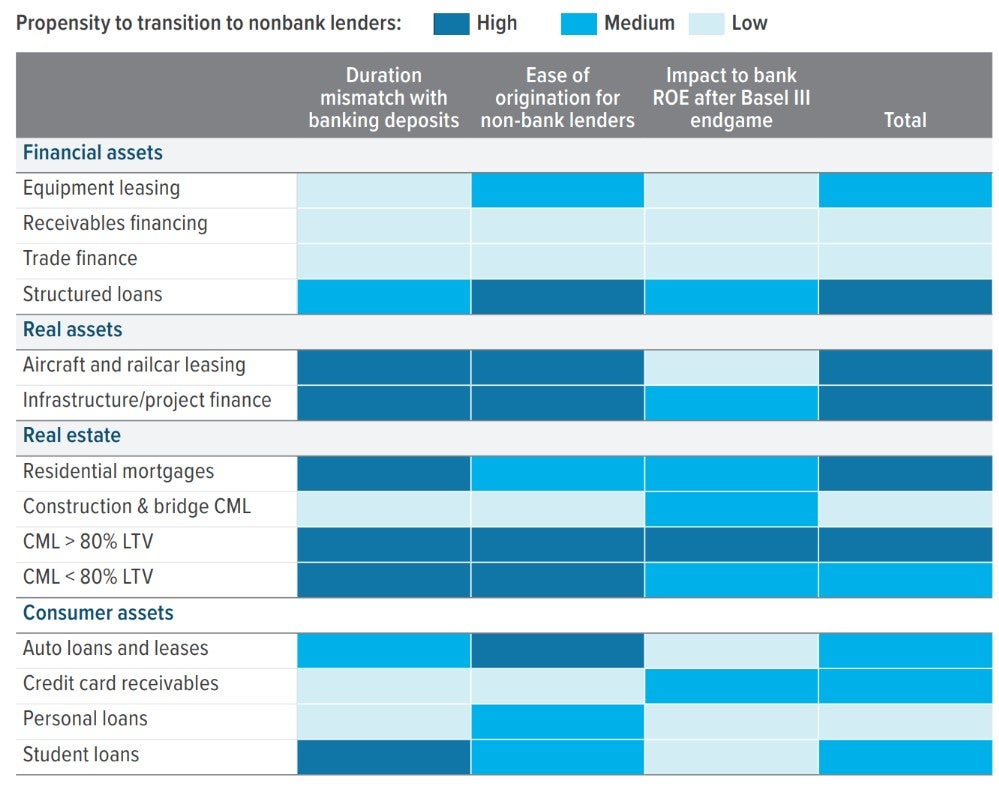

On the borrower side, banks have heavily pulled back from structured lending areas they used to dominate, largely due to ongoing changes in banking regulation that began in response to the global financial crisis (Exhibit 2). Specialty, non-bank lenders like us have been filling some of the demand gaps. This has accelerated following 2023’s regional bank collapses.

As of 09/30/24. Source: McKinsey.

For example, one of the highest-quality loan types in the fund finance vertical are subscription lines. You’re lending short term against cash commitments from a range of high-quality LPs. Most private funds have sub lines and, as we all know, private assets under management have increased massively over the past 10 years, so demand keeps rising.

The sub line lending space was dominated by three banks: Silicon Valley Bank, First Republic, and Signature Bank. Those banks ceased to exist in early 2023. But the demand for sub lines did not cease to exist—and while sub lines historically tended to be revolving facilities rather than term loans, more and more borrowers have begun accepting term-loan-style structuring so that they can tap the non-bank lending market.

On the lender side, several large private-equity-linked non-bank originators have entered the market, filling 60-80% of their insurance subsidiaries’ fixed income portfolios with private deals and buying multiple origination platforms.1 These companies now have predictable forward flows, thanks to those origination platforms, and are naturally marketing the ABF securitizations of those flows.

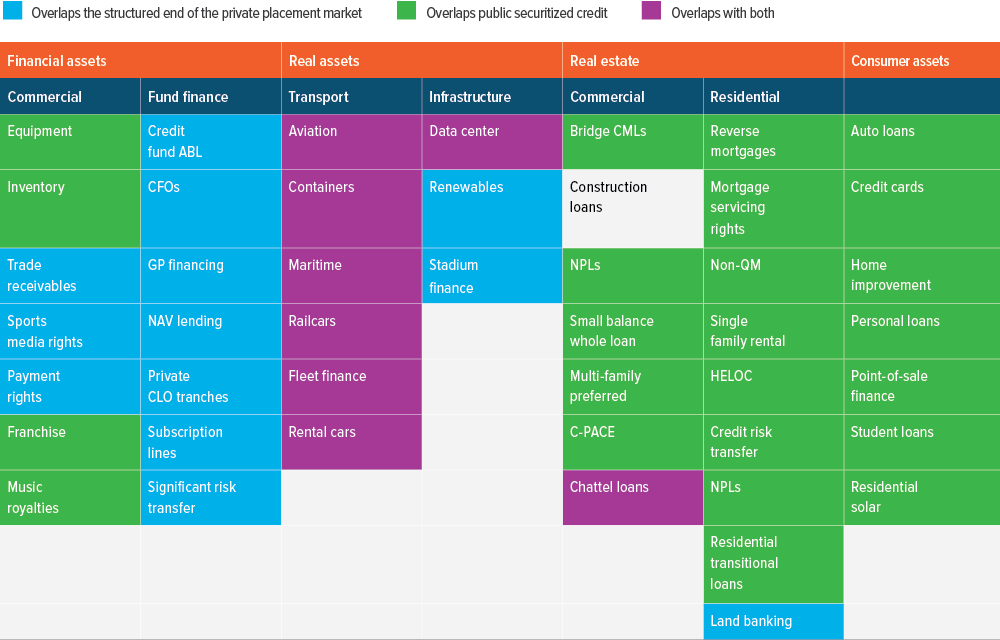

ABF and its relatives: Securitized credit and private credit

If there’s a perfectly good public securitized market out there, why isn’t it taking these deals? The borrower would certainly save money by going public.

There’s a private ABF market for the same reasons that there’s a private corporate placement market: A significant amount of borrowers want some combination of privacy and customization that the public markets can’t provide, and they’re willing to pay to get it.

The private ABF market tends towards smaller or middle market enterprises with distinctive segments of asset classes that don’t fit the public securitized market well.

The public securitized market likes large deals that all look like each other, with consistent kinds of collateral pools. Whether it’s consumer loans or resi mortgage or commercial mortgage, they want it all to be structured the same way.

Borrowers pay more for private ABF, but they can get a guaranteed close, delayed draws, and special terms, and they can borrow against assets that may take considerable effort and research to underwrite. Private non-bank lenders are willing to do that: we led a securitization of hydrocarbon reserves where we brought in an independent engineer to help us more effectively ring-fence transaction cash flows, and we got the transaction to 30% overcollateralization and a DSCR of 1.3x.

For non-bank lenders such as ourselves, ABF allows us to set up the terms that we want, versus the “take it or leave it” of a public deal. We can get to specific covenants, specific maturities, or specific ratings. We can make adjustments to the collateral pool. This allows for both more robust underwriting and better customization to client needs.

Here’s an example. An aircraft securitization deal came to market a few years ago, and Voya was among the first ABF lenders approached. We initially passed on the transaction because we didn’t like the collateral pool—too many of the included aircraft were registered in emerging market jurisdictions that would likely be unfavorable to creditors in the event of default. We were shown the deal again a little later, and, because we had the potential to bring considerable money to the table, we were able to improve the collateral selection and introduce several other creditor-friendly changes to the structure.

Another advantage of ABF is that you can tailor deals to the liability duration needs of large clients. A deal intended as 10-year paper can often have tranches created specifically to match client liabilities that are shorter or longer than 10 years.

In short, the customization possibilities of the private market benefit everyone involved.

Also, don’t discount privacy as a motivation. Looking at fund finance again, can you imagine publicly placing an NAV loan? All that previously GP- and LP-only information, just out there for anyone in the public market to read and comment on? Anyone heavily invested in PE right now probably felt their blood pressure rise just reading that.

What’s distinctive about ABF, compared with investment grade private placements?

Compared with investment grade private placements, ABF offers:

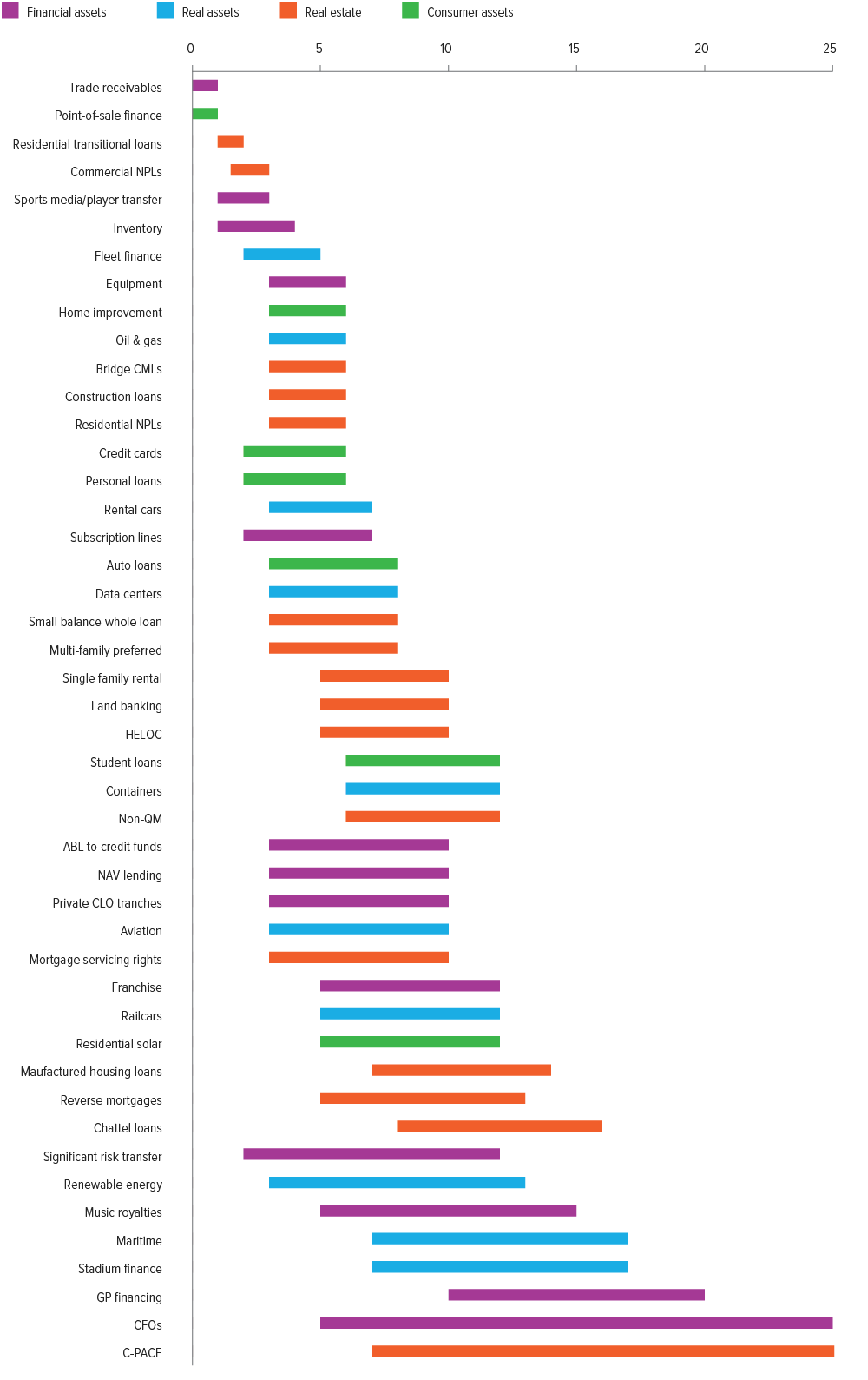

- Exposure to different collateral categories, such as consumer assets, commercial real estate, and residential real estate, as well as more structured exposure to traditional private credit categories like financial assets and infrastructure lending.

- A high proportion of floating-rate paper with a weighted average life (WAL) of 5 years or less, versus corporate placements’ fixed rate, 8-12 year WAL (Exhibit 3).

- Self-amortizing structures that provide consistent deleveraging, versus corporate placements’ tendency to require a liquidity event (refinance of debt, sale of assets) for repayment.

ABF is actively quite exciting for P&C insurers, who previously struggled with the 7-10 year duration profile of most investment grade private placements. Really, for any client who needs to redeploy cash more regularly than most corporate placements allow, ABF is a game changer.

For clients who have longer-duration liabilities, the ABF or highly structured end of infrastructure placements can help extend duration profiles. And if the other, shorter-leaning collateral classes appeal, managers can work with a transaction’s sponsor to see if they are willing to create a tranche that has a longer duration for a specific client. There are often multiple tranches or multiple investment opportunities within a specific transaction, and some might fit better for one client type more than others.

As of 08/10/25. Source: Voya IM estimates.

The ABF allocation process

Is all ABF investment grade?

No. ABF is primarily investment grade, but there are some transactions that will be sub-investment grade. Some individual transactions also offer residual and subordinated pieces alongside investment-grade senior tranches. There are opportunities to take non-investment grade risk for those clients whose goals that would fit.

Is ABF illiquid?

It’s semi-liquid, similar to investment grade private placements—it’s easier to sell than to buy. We estimate it normally takes around two weeks to sell out of a single name at market price. The usual secondary buyers are co-investors who like the deal and may be interested in adding to allocations, as well as investors who were not able to get into the deal in the first place.

But it’s like anything in private assets: Being selective and obtaining access to the highest-quality and most in-demand deals will give you more liquidity options than taking plain vanilla placements or getting wrapped up in a trust where you don’t have control over what’s going into it.

There are also active efforts to create a secondary market in private ABF, so we feel comfortable saying that we think ABF liquidity will only improve.

How should investors think about allocating to ABF? What does it replace?

ABF allocation is a custom process that depends heavily on clients’ liability profiles, liquidity needs, and existing allocations to private assets.

Longer-term investors, such as insurers, will know from scenario analysis and stress tests what is a safe amount to place in semi-liquid private assets like ABF.

So first it’s a question of: Do you have room to expand your allocation to private assets in order to take advantage of ABF’s spread premium? Or are you trimming other allocations or redeploying capital to invest in ABF?

Then it comes down to asset/liability mix. What risk profile do you want to be in? What duration are you aiming for? And do you have any sector limitations on ABF that correlate to your existing public mandates, or to existing private allocations such as CMLs? If you already have a large CML allocation, you probably don’t want an ABF portfolio that also includes CMLs.

Investors can also consider whether the source of the return premia for a specific fixed income sector can be better gleaned in ABF. Would being secured by equipment in a structured ABF transaction offer better risk-adjusted returns than buying the bonds of an investment grade rated equipment lessor? Can you earn the same returns on a senior fund financing transaction backed by low-leveraged private credit collateral as through mezzanine tranches of a CLO backed by increasingly covenant-lite collateral?

As of 08/15/25. Source: Voya IM.

Market risks and concerns

There have been some bullish growth numbers around ABF recently. Are we in a bubble?

The classic warning sign for a credit bubble is when a sector’s borrowing levels rise rapidly—because debt problems soon follow. We saw this in technology, media, and telecom just before the tech bubble; in the financial sector ahead of the global financial crisis; and in the shale patch in the middle of the last decade. The rise of ABF is not the result of an overall rise in indebtedness, but a shift in who is supplying that debt.

Does that mean all ABF lending will be done well? Of course not. But we believe any problems are likely to arise at the individual deal/underwriting level, rather than as a result of systemic issues in the market.

The biggest impact of having more investors allocate to ABF is likely the same as what’s happened in the investment grade private placement market, which is downward pressure on spreads in the more plain-vanilla side of the market. These are imperfect markets, and one of the ways that plays out is who gets the call when deals come to market. Tier One managers who can sign $350-500 million checks get called first, while those who can only sign $10-20 million checks get called last or not at all. And so the most in-demand deals tend to stay within a group of large players and their clients.

It’s also worth noting that banks are starting to reenter the ABF market due to some of the regulatory changes being discussed by the current administration. But one of the ways they’re getting back into the space is by providing back leverage at the senior level to these underlying loans, rather than making loans directly.

What should investors be concerned about in the ABF space?

There are three main areas of concern:

- Managers overpromising their ABF capabilities and then underdelivering.

- Banking regulatory relaxation incentivizing banks to get back into the asset-based lending business in a big way.

- Owners of captive origination platforms focusing on volume rather than quality.

On the overselling front, some of the firms hyping ABF the most haven’t been doing it long enough to hold a single placement through to maturity. There is a risk that those managers end up not providing enough diversification and/or not enough spread, adjusted for fees, or that they may face underwriting issues. We think investors may be best served by hiring multiple managers in the space with differentiated sourcing, deal focus, and even delivery mechanisms (e.g., funds versus SMAs).

Part of the ABF thesis has been that there’s an attractive opportunity due to pullback in lending by commercial banks (Exhibit 2). The flip-side risk is that regulatory change by this administration may change banks’ tactics towards this market.

Banks can be simple creatures. Sometimes they’re in the storage business—holding loans on their balance sheets. And sometimes they’re in the moving business—syndicating those loans to non-bank players like us.

If banks get back in the storage business in a big way, while a lot of capital has been raised to invest in ABF managed by non-bank lenders, then you could end up with a lot of bodies chasing smaller-than-expected deal flows. Whenever that happens in capital markets, there’s downward pressure on spreads, and this tends to cause people to reach for risk.

This also has implications for origination platforms. A big trend in asset manager M&A recently has been acquisitions of origination platforms. These platforms get taken offline, and the new owner ends up with captive origination that got bought at a premium valuation.

In many cases, this works out well and brings useful flows into the ABF market. But any experienced M&A professional will tell you that not every acquisition ends in sunshine and rainbows. There may be cases where a particular platform struggles and/or is less discerning on spread and delivering relative value.

Investors should stay watchful and make sure they have the ability to say no to deals they don’t like, even if those deals come from origination platforms owned by their ABF manager.

A note about risk: All investing involves risks of fluctuating prices and uncertainties of rates of return and yield. All security transactions involve substantial risk of loss. Private credit and ABF: Foreign investing does pose special risks, including currency fluctuation, economic, and political risks not found in investments that are solely domestic. As interest rates rise, bond prices may fall, reducing the value of the share price. Debt securities with longer durations tend to be more sensitive to interest rate changes. High yield securities, or “junk bonds,” are rated lower than investment grade bonds because there is a greater possibility that the issuer may be unable to make interest and principal payments on those securities. Other risks of private credit include, but are not limited to: credit risks, other investment companies risks, price volatility risks, inability to sell securities risks, and securities lending risks.