Liability management exercises may offer a quick fix for financially distressed companies, but they can sometimes make bad situations worse, underscoring the importance of rigorous credit research and security selection.

The rise of LMEs as a bankruptcy alternative

Over the past few years, there’s been a notable shift in the way borrowers—mainly sponsored issuers—approach financial distress. Instead of reorganizing their capital structure through the traditional Chapter 11 bankruptcy process, more borrowers are opting for liability management exercises (LMEs) as an alternative “out-of-court” route for restructurings.

LMEs have been around since financing markets for leveraged borrowers have been open, but they’ve only recently gained popularity among stressed companies amid the growing need to manage looming maturities and higher interest burdens in the wake of the Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate-hike campaign post Covid.

For borrowers, LMEs can be a more flexible and efficient way to restructure, allowing them to negotiate terms without submitting to a lengthy and costly bankruptcy process. These exercises typically involve debt-for-equity swaps, debt buybacks, or maturity extensions, helping borrowers reduce liabilities and improve their balance sheets. As a result, LMEs facilitate quicker resolutions, preserve equity value, and avoid the public scrutiny and disruption that can accompany formal bankruptcy filings. That makes them an attractive alternative for sponsors in today’s financial environment.

Different types of LMEs, different consequences

LMEs are typically categorized into traditional (non-coercive) and coercive types. Traditional LMEs, such as amend-and-extends, tender offers, and buybacks, are well-established debt management tools that have been used extensively in the market. Coercive LMEs, by contrast, reflect the evolution of looser documentation and a greater willingness by sponsors to engage in more complex activities that could potentially benefit one set of lenders at the expense of others, such as:

- Uptiering—Involves introducing new senior-priority loans that rank above the existing debt stack, often leaving non-participating lenders with subordinated collateral, which can significantly impact their recoveries.

- Asset dropdowns—Involve transferring assets to a new entity that incurs its own debt, potentially reducing the assets available to the original entity and its creditors, thus impairing future recovery.

- Double dips—Occur when new debt is created with claims against the same pool of assets as existing debt, often through intercompany loans and guarantees. This structure can result in multiple layers of claims for new creditors, diluting the position of existing creditors. While a double dip is generally considered less coercive than an uptiering, it still introduces risks and complexities for lenders.

Lenders strike back

This evolution of the LME landscape has led to the rise of the “co-op agreement,” in which ad hoc lender groups form to consolidate a majority stake in one or more tranches of an issuer’s capital structure. By doing so, these lenders gain leverage and the ability to safeguard their positions in the event of an LME. The flexibility of co-op agreements allows them to serve dual purposes: they can act defensively to protect lenders from potential losses or offensively to influence the outcome of a distressed situation.

The emergence of co-op agreements has altered borrower/credit dynamics and impacted the secondary loan market for the respective issuers, with different trading levels for “co-op loans” and “non-co-op loans.” The co-op/non-co-op price differential tends to be idiosyncratic and is often influenced by supply/demand drivers and stipulations in the co-op agreement.

Default trends have diverged

In recent years, the gap between the standard default rate (which reflects payment default activity) and the default rate that includes distressed exchanges has widened significantly. According to market data provider LCD, the trailing 12-month count of LMEs has outpaced payment defaults and bankruptcies every month since the start of 2024. This demonstrates a substantial increase in the proportion of defaults occurring via LMEs, which have become a dominant form of restructuring.

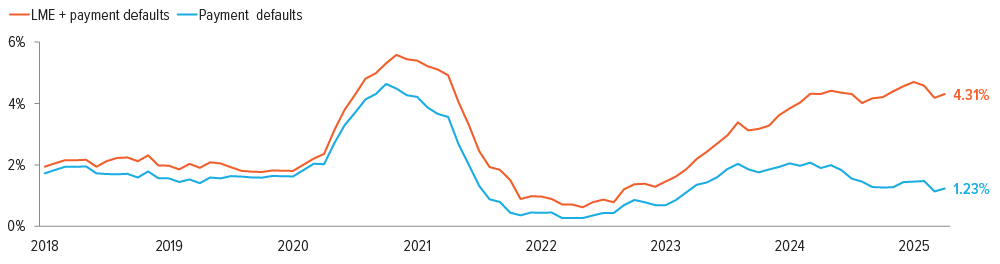

In the 12 months ended March 31 2025, the LME default rate by issuer count (Morningstar LSTA U.S. Index) was 3.08%. Since 2019, more than half of U.S. defaults have been distressed exchanges. With sizable defaults rolling off the last-12-month calculations, the payment default rate excluding LMEs dropped to 1.23% in March. However, looking at both LMEs and payment defaults, the combined issuer count default rate was 4.31%, a marked increase from three years ago, though below December’s elevated level of 4.70% (Exhibit 1).

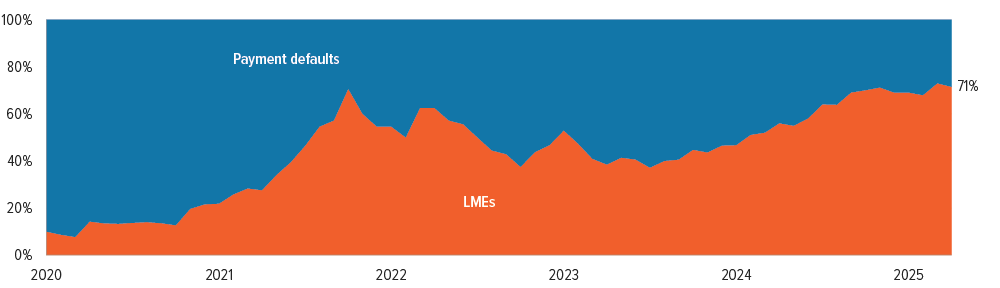

Over the same 12-month period, LMEs have accounted for 71% of restructurings, near an all-time high (Exhibit 2). Private-equity-sponsored companies continue to drive LME activity, though nonsponsored companies have recently outpaced them in payment defaults. The preference of sponsorbacked companies to restructure via LMEs—which tend to preserve the equity stake held by private equity funds—remains strong. Sponsored companies represented 78% of LME transactions over the last 12 months, from 91% in 2023.1

As of 03/31/25. Source: Pitchbook | LCD, Morningstar LSTA U.S. Leverage Loan Index, Voya IM.

As of 02/28/25. Source: Pitchbook | LCD, Morningstar LSTA U.S. Leverage Loan Index, Voya IM.

Outlook on LMEs

We expect that LMEs will continue to dominate the market and keep default rates elevated, as looser documentation trends and high interest rates persist.

Distressed exchanges can sometimes yield more positive outcomes in terms of recovery rates, but many companies employing LMEs are effectively postponing their financial distress and will eventually file for traditional bankruptcies. According to LCD, during the Covid-related default wave of 2020, nearly a quarter of issuers that completed a distressed exchange/LME returned to traditional defaults— including missed interest payments and bankruptcy filings—within three years.

The takeaway: Although distressed exchanges may provide temporary relief, they often delay the inevitable, ultimately leading to more substantial financial challenges down the road. As such, these developments highlight the need for careful security selection in what remains an evolving landscape.

A note about risk

Principal risks for senior loans: All investing involves risks of fluctuating prices and the uncertainties of rates of return and yield. Voya’s senior loan strategies invest primarily in below investment grade, floating rate senior loans (also known as “high yield” or “junk” instruments), which are subject to greater levels of liquidity, credit, and other risks than are investment grade instruments. There is a limited secondary market for floating rate loans, which may limit a strategy’s ability to sell a loan in a timely fashion or at a favorable price. If a loan is illiquid, the value of the loan may be negatively impacted, and the manager may not be able to sell the loan in order to meet redemption needs or other portfolio cash requirements. The value of loans in the portfolio could be negatively impacted by adverse economic or market conditions and by the failure of borrowers to repay principal or interest. A decrease in demand for loans may adversely affect the value of the portfolio’s investments, causing the portfolio’s net asset value to fall. Because of the limited market for floating rate senior loans, it may be difficult to value loans in the portfolio on a daily basis. The actual price the portfolio receives upon the sale of a loan could differ significantly from the value assigned to it in the portfolio. The portfolio may invest in foreign instruments, which may present increased market, liquidity, currency, interest rate, political, information, and other risks. These risks may be greater in the case of emerging market loans. Although interest rates for floating rate senior loans typically reset periodically, changes in market interest rates may impact the valuation of loans in the portfolio. In the case of early prepayment of loans in the portfolio, the portfolio may realize proceeds from the repayment that are less than the valuation assigned to the loans by the portfolio. In the case of extensions of payment periods by borrowers on loans in the portfolio, the valuation of the loans may be reduced. The portfolio may also invest in other investment companies and will pay a proportional share of the expenses of the other investment company.

Principal risks for high yield bonds: All investing involves risks of fluctuating prices and the uncertainties of rates and return and yield inherent in investing. High yield securities, or “junk bonds,” are rated lower than investment grade bonds because there is a greater possibility that the issuer may be unable to make interest and principal payments on those securities. As interest rates rise, bond prices may fall, reducing the value of the portfolio’s share price. Debt securities with longer durations tend to be more sensitive to interest rate changes than debt securities with shorter durations. Other risks of the portfolio include, but are not limited to, credit risk, other investment companies risks, price volatility risk, the inability to sell securities, and securities lending risks.